What Am I Made For? Barbie Goes Beyond The Battle of the Sexes

“I don’t know how to feel, but I wanna try.”

~ Barbie speaks through Billie Eilish

At the end of the movie Barbie, Ruth Handler (creator of Barbie) tells Barbie: “You should not take this leap into the real world unless you know what this means.”

Ruth gently holds Barbie’s hands. She asks Barbie to close her eyes and feel, and Barbie sees images of girls and women of various ages. She sees (as do we) images of mothers and children embracing, connecting, playing, and bonding. This montage – made from footage that Gerwig sourced from the film’s cast and crew, fills Barbie with emotion as she understands the full scope of womanhood, including birth, childhood, motherhood, and generational love. We see the entire life cycle as a female human being and the expressions of female emotions. It is quite beautiful. Barbie says, “Yes,” she wants this.

“I Don’t Know How to Feel, But I Want to Try”

As the video montage runs, the movie is essentially over; it is easy to dismiss or not fully “see” this fleeting black-and-white montage — or truly savor the haunting melody and poignant lyrics of Billie Eilish singing, What Was I Made For? The images are more profound because of this background music. Eilish wrote this song specifically for Barbie in an immersed zone of connection; she channels the critical message at the movie’s end with this chorus: “I don’t know how to feel, but I wanna try. I don’t know how to feel, but someday I might.”

Please watch and listen to the video. (Lyrics in video and in the Appendix.)

Barbie Enters the Human World of Mate Selection and Sexuality

Barbieland is asexual and non-maternal; it has no children. The entire film is devoid of young children until the scene with Ruth. When stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) goes to the real world, she owns her sexual reproductive instincts and visits the gynecologist. She enters the real world of mating and dating; Barbie must begin to swim in the streams of heterosexual dynamics with men.

Sexual Reproduction and Motherhood Are Aspirational

The real-world “Kens” come fully equipped, and they do know (unlike Kens in Barbieland) why they might want to sleep over with Barbie. This is the world that Barbie must navigate to fulfill Ruth’s assertion and promise. Sexual reproduction and motherhood are included in the mix of aspirations for Barbies to be anything they want to be.

Gerwig and Motherhood

During the writing of Barbie, Greta Gerwig was nursing and attending to her new baby boy, Harold, with partner Noah Baumbach. Gerwig and Baumbach had another baby boy in March 2023. So, two kids were on the Barbie promotion circuit under the watchful eye of their mother. Suffice to say, being a mother is one crucial element of Gerwig’s personality. Mattel discontinued Pregnant Barbie, but Gerwig had not lost sight of this part of the female experience, even though there is no maternal instinct in Barbieland. (Gloria and Sasha represent a central mother-daughter plot in the real world.)

Feminism Includes Motherhood

Gerwig is undoubtedly not endorsing a return to 1950s motherhood – being a wife and stay-at-home mother (often pregnant). Gerwig’s feminism includes maternity as an option. It is part of the natural order for many women, even women with creative, full-time careers.

“In creating Barbie,” Ruth Handler explained, “my philosophy was that, through the doll, girls could become anything they wanted to be. Barbie has always represented a woman who chooses for herself.”

Barbies Do Not Have an Ending, But Humans Do

Ruth tells Barbie: “Humans only have one ending. Ideas live forever.” Barbie accepts that she will die. Barbie says “yes” to entering the real world because the experience of human emotion is what we are made for.

Old Woman on A Bench

In one scene, Barbie sees an old woman on a bench and tells her, “You are beautiful.” The woman says, “Yes, I know.” This is not a commentary on physical attractiveness or even the inner beauty of older people; it is an endorsement of the beauty of the full spectrum of human experience.

Barbie Wants to Imagine as Subject, Not Object

“I want to be the one imagining, not the idea.”

When Barbie decides whether to return to a worry-free life or experience humanity (the opposite), she says, “I want to be the one imagining, not the idea.” Barbie’s desire to be subject, not object, is a longing felt by human women whose worth in society is often measured by how aesthetically pleasing they are to men. (Many women have a place in their sexuality for being “object,” but that is another topic.) Barbie would be more objectified in the real world than in Barbieland, so why does she want to be human?

Female Emotion as a Strength

The reason to be human is the exaltation of feeling the range of human emotions, especially as a woman. The ending to Barbie shows women’s emotions as a strength, not a weakness. A central thesis of Barbie may be that emotion isn’t just an accessory to the human experience – it plays a vital role in making the human experience worthwhile.

Barbie Wants the Human Experience – She Wants “Ubuntu”

“Ubuntu” is a South African term popularized by Desmond Tuto. Ubuntu means “I am what I am because of who we all are.” You cannot exist as a human being in isolation. We are interconnected. People are not people without other people.

We Even Need People We Have Never Met

Barbie experiences memories of people she has never met, but that’s the whole point: We don’t have to know the women in the montage to resonate with them. Female moviegoers across the globe connected to this scene in ineffable ways – they cried together, not always knowing why they were sad or moved. (Men cried too, empathizing with the spirituality of the human experience, longing for their mother, or even longing for their father and a similar intergenerational bond between boys and men.)

The Infinite Chain

The essence of womanhood and humanity has nothing to do with careers or pink outfits. By taking Ruth’s hand, Barbie becomes another link in an infinite chain of mothers and children. She glimpses a sweet intergenerational heritage of beings incarnated as Homo sapiens — an experience not available to her as a fictional construct. Barbie feels a spiritual connection between generations of women, passing down their hopes and dreams for a better world. Barbie becomes human.

Now She is Barbara Handler

Final scene: Barbie walks up to a reception desk (in her pink Birkenstock sandals) and says: “I’m here to see my gynecologist.” Barbie is now “Barbara” and part of the legacy of female creation and personhood. She’s a Handler now, like Ruth.

Barbie’s Transition: Maslow’s Hierarchy and Attachment Bond

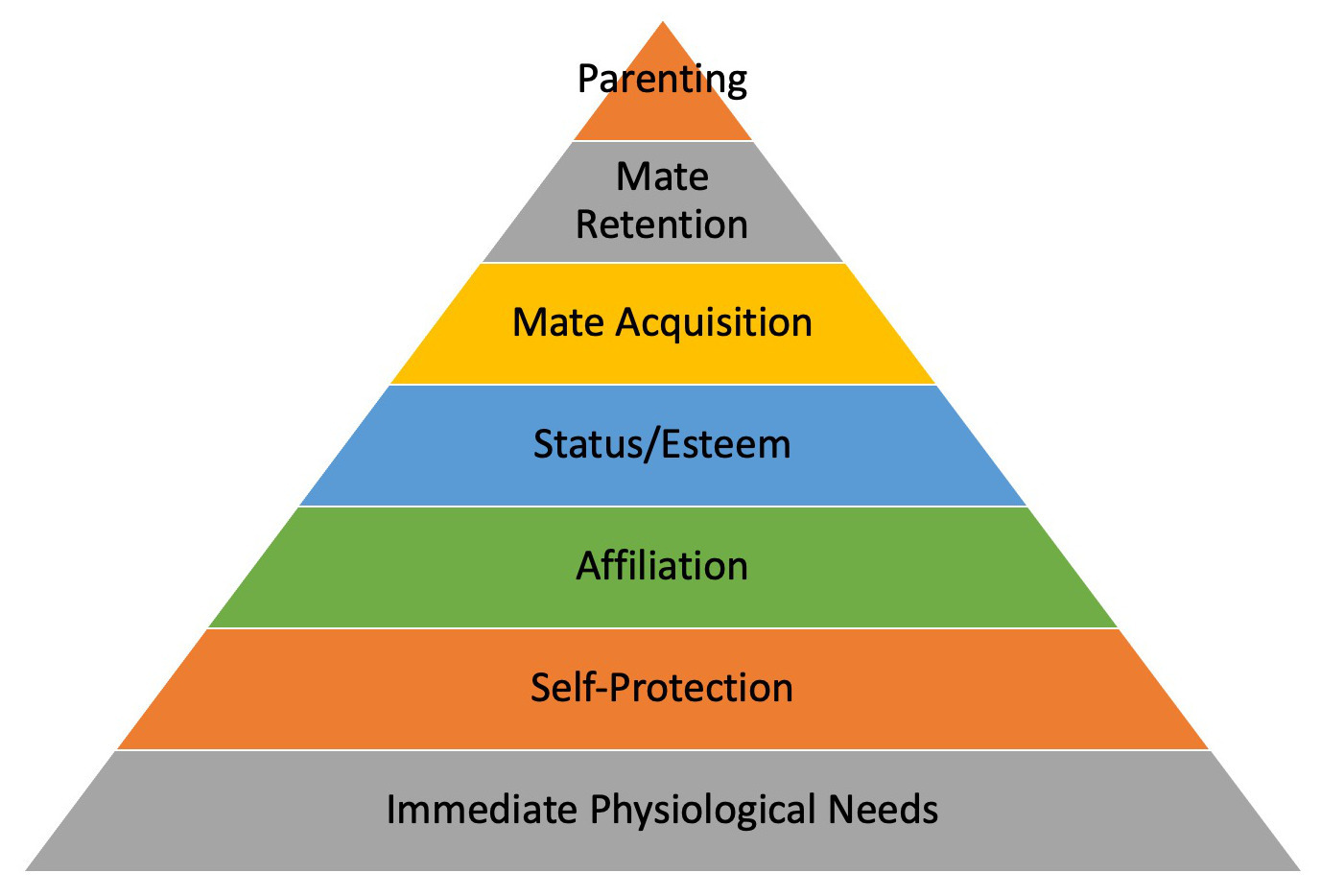

Briefly shifting gears, please allow me to connect Barbie to psychological theory. You might be familiar with Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow believed that we begin life by trying to satisfy physiological and social motives (love, belonging, and esteem /respect), which he viewed as deficiency needs. If you fulfill those deficiency needs, you can move on to growth needs; the highest level is self-actualization. Maslow’s work was done before the modern integration of evolutionary biology and psychology, so he gave no attention to the central Darwinian themes of reproduction. Maslow gave incomplete attention to one of the essential elements of Barbie’s transition — the preeminence of the attachment bond between mothers and children.

Barbie and the New Hierarchy of Human Motivations

After studying the evolutionary psychology of human motives for 20 years, psychologist and researcher Douglas Kenrick (Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain) updated Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to reflect developments in the behavioral and biological sciences. Self-actualization was removed from its hallowed place at the top.

Finding Mates, Retaining Mates, and Parenting

The new hierarchy of human motives addresses the missing goal that is paramount from a Darwinian perspective, adding three more layers associated with reproduction: finding mates, retaining mates, and parenting. In this new model, the seven human needs or motivations are not stacked on top of one another but are seen as overlapping. Yet, Kenrick suggested that kin care, or parenting, is the ultimate goal of humanity.

What Was I Made For?

According to Kenrick, if you have young children, parenting motives become increasingly linked to your sense of self-actualization and meaning in life. Cue the Barbie movie montage of women, relationships, and human emotions. Cue the Billie Eilish song. This answers Barbie’s question: what was I made for? You were made for acquiring a mate, retaining a mate, and taking care of your family (and the families of all women) with all its attendant joys and pathos. Ruth holds Barbie’s hands and shows her that this is what it means to take the leap from Barbieland into the real world of humanity.

Postscript: What I Left Unsaid About Barbie (related to the film’s message, not its production)

This post and my last post on Barbie (Unpacking Barbie’s Apotheosis – Which Complaints Hold Up Under Scrutiny?) can be seen as bookends in tone: embracing and honoring the human-female experience vs. a detailed critique of Barbie’s central feminist message. But there is a lot left on the table to talk about; I just choose to move on.

Left unsaid and not fully discussed by me:

- Barbie’s misandry (the movie is anti-male on the surface): no men in Barbieland or in the real world have any redeeming qualities. They are portrayed as silly, stupid buffoons — superfluous for the most part and oddly attached to horses. (Allen is a special case that does not disprove the point.)

- After the Barbies retook Barbieland, it was close to an apartheid state for men. Men will have no voice or real representation — less representation than women in the real world. (It is unclear if the Kens get places to live.)

- Barbies use trickery and their erotic power over men to retake Barbieland. They lie to the men when they act interested in what the men are saying or singing. Barbies strategically use jealousy (intra-sexual competition) between the men to cause them to fight one another. (This is of course common in the real world, but it is almost interesting here, given Barbieland is supposedly an asexual environment.)

- Relatedly, Barbies exploit male fragility; the movie does have relevant things to say about the fragility of men. Kens need a Barbie more than Barbies need a Ken. There is an existential threat to men if they are not sexually acceptable to a woman. Ken: “I only exist within the warmth of your gaze.” And, “Barbie has a great day everyday, but Ken has a great day only if Barbie looks at him.” Ultimately, Ken might be “enough” of a nice guy, but he will not be a suitable sex partner or mate. Barbie is not interested. Full stop.

- There are perhaps relevant reflections (and reviews to share) about non-binary gender presentation and even implied queer sexual preference in Barbie.

- There is a rise of bimbo feminism (especially on TikTok) in response to this movie – the combination of hyper-femininity and feminism.

- There is a message about patriarchy via Mattel’s corporate capitalism windfall.

- There is a twist on the creation myth: analog to the Garden of Eden and Adam and Eve.

- There is a possible connection in the Barbie video montage to the alloparenting instinct – pair bonds with fellow female alloparents who help raise children. (see It Takes a Village – Alloparenting and Female Sexual Fluidity.

Final thoughts: Barbie is Allegory and Satire

Given all this, it is important to remember that the movie Barbie is an allegory and satire. Greta Gerwig is a sly filmmaker. As the marketing promotion said: if you love Barbie, you will love this movie. If you hate Barbie, you will love this movie. But you might hate this movie in both cases. Not me. I was intrigued and stimulated more than I wanted to be. I cannot hate that.

Appendix

What Was I Made for – Lyrics by Billie Eilish

I used to float, now I just fall down

I used to know but I’m not sure now

What I was made for

What was I made for?

Takin’ a drive, I was an ideal

Looked so alive, turns out I’m not real

Just something you paid for

What was I made for?

(Chorus)

‘Cause I, ’cause I

I don’t know how to feel

But I wanna try

I don’t know how to feel

But someday I might

Someday I might

When did it end? All the enjoyment

I’m sad again, don’t tell my boyfriend

It’s not what he’s made for

What was I made for?

‘Cause I, ’cause I

I don’t know how to feel

But I wanna try

I don’t know how to feel

But someday I might

Someday I might

Think I forgot how to be happy

Something I’m not, but something I can be

Something I wait for

Something I’m made for

Something I’m made for