A wise skepticism is the first attribute of a good critic.

~ James Russell Lowell (1819-1891)

In This Post (Strands of Rope)

- Jonathan Haidt’s constructive criticism of Democrats

- Challenges and miracle of e pluribus unum – “out of many, one”

- Problems with “defund the police” messaging

- Disagreements with Haidt’s portrayal of the moral matrices

- Dangers of “moral capital” and potential failures of the Conservative moral matrix

- “Yin and yang” interdependency of our political affiliations

- Guiding philosophies of John Stuart Mill and Emile Durkheim

- Human’s dual nature, “hive switch,” and “collective effervescence”

- Football games and religious rituals

- Belonging is more important than beliefs; belonging is essential to humans

Introduction

In my last post, Our Political Divide – Part 4: Moral Foundations – A Path To Understanding, I described six moral foundations that undergird and inform the political affiliations of liberals, conservatives, and libertarians. Based on the work of Jonathan Haidt, I also outlined the moral matrices of liberals, conservatives, and libertarians, using bar graphs to demonstrate the relative strength of each foundation – a unique profile for each political affiliation. Part 4 explained what liberals and conservatives really care about. This post will assume that the reader has some familiarity with the six foundations and perhaps the “Ten Insights from Jonathan Haidt” presented in Political Divide – Part 3: Review and Introduction to the Moral Foundations.*

Why is this Information Important?

Understanding what liberals, conservatives, libertarians, and activated authoritarians care about gives a framework for empathic communication – an opening for conflict de-escalation, problem-solving, reconciliation, and unification of communities in the United States. Stay tuned for my final post in this series, Political Divide, Part 6: Moral Communication — the Way Forward.

Biggest Partisan Difference

Haidt claims that liberals primarily use three foundations – Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, and Liberty/oppression, whereas conservatives utilize all six. According to Haidt, the foundations of Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation are equally salient in conservative morality. Haidt contends that liberals are ambivalent about Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity. He says this is the most significant partisan difference between liberals and conservatives.

Democrats – Listen Up

Twelve years ago, Haidt warned Democrats about “deficiencies” in their moral framing to the American electorate. It bears repeating and considering.

Close the Sacredness Gap

Democrats, he said, must find a way “to close the sacredness gap” between themselves and Republicans. Haidt references sociologist Emile Durkheim in recognizing that sacredness is about society and its collective concerns. These concerns are embedded in the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations. Democrats could close much of the sacredness gap, Haidt says, if they saw society not as a collection of individuals but as an entity in itself.

Why Do Working Class and Rural Americans Vote Republican?

Voters do not vote for their self-interests; they vote for their values. Working-class and rural Americans don’t want their nation to devote itself primarily to the care of victims and the pursuit of social justice, asserts Haidt. Until Democrats understand the difference between a six-foundation and three-foundation morality, they will not understand what makes people vote Republican.

“Out of Many, One” – It’s Complicated

Our national motto is e pluribus unum – “Out of many, one.” But political scientist Robert Putnum (Bowling Alone) found that ethnic diversity (in the short run), increased alienation and social isolation by decreasing people’s sense of belonging to a shared community. People tend to “hunker down,” he says. Trust (even of one’s own race) is lower, altruism and community cooperation decline.

Difficulty Binding the Many – the Problem with E Pluribus Unum

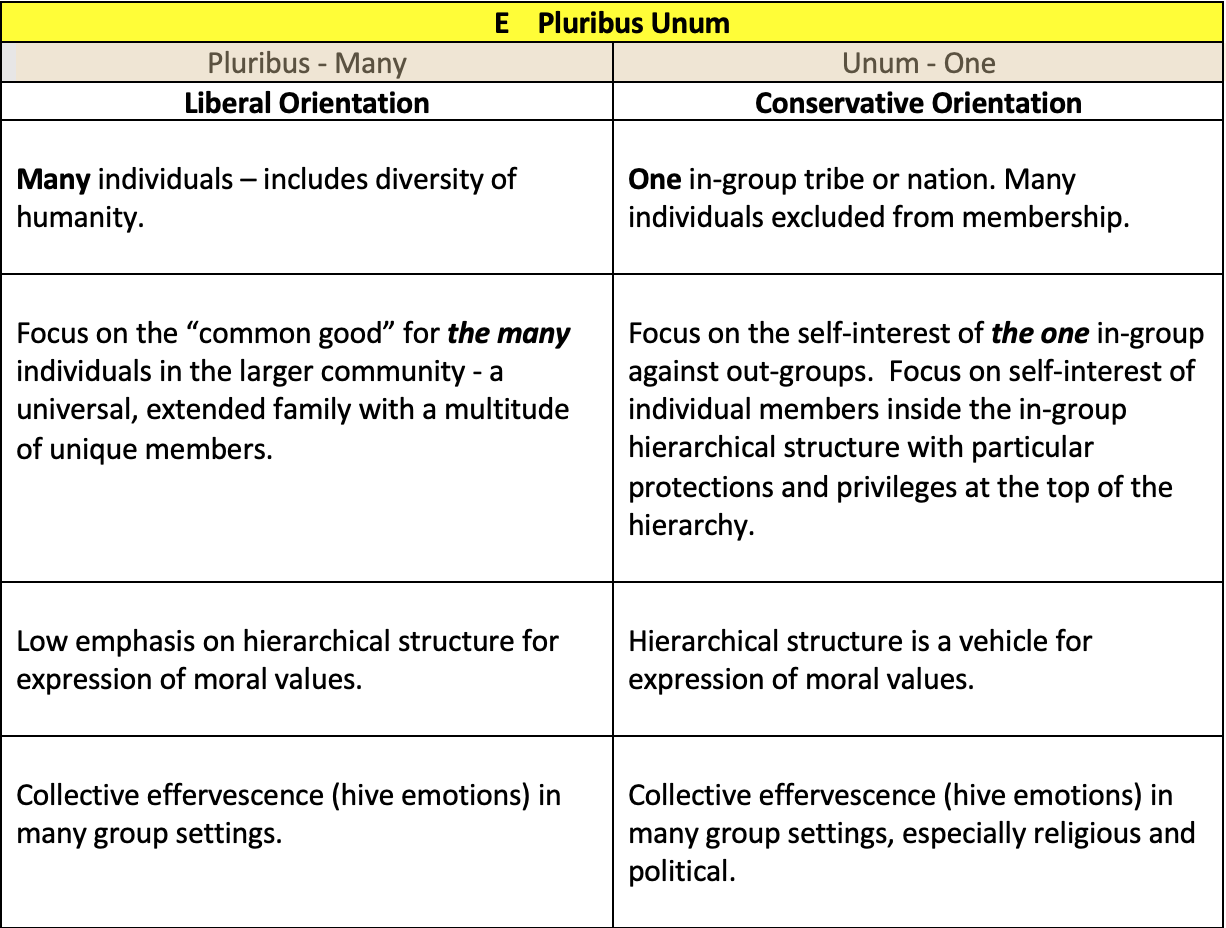

Haidt says liberals have difficulty binding pluribus (the many individuals) into unum (the one, collective, in-group.) He says Democrats pursue policies for the many at the expense of the one.

Don’t Weaken the Collective

In 2008, Haidt suggested that diversity programs to fight racism and discrimination might be better served by encouraging assimilation and a sense of shared identity. He asserted that progressive policies of multiculturalism, bilingualism, and immigration demonstrate that Democrats care more about pluribus than unum. They weaken the integrity of the collective; they widen the sacredness gap. These ideas of Putnam and Haidt might be hard to take in the current era of liberal “wokeness.” And Haidt might revise this advice in 2021. But, perhaps Democrats should revisit and reflect on this critique.

The “Many” In-group

Conservatives are more concerned than liberals about group cohesion as sustained by their most prized morality foundations: Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation. Conservatives are worried about the many (individuals) as long as it is their in-group and not an out-group, whereas liberals are concerned about everyone, inside the group and outside the group.

Moderate Doses of the Loyalty Foundation

The Loyalty foundation supports a kind of patriotism and self-sacrifice that can lead to dangerous nationalism. But in moderate doses, it can lead to a sense that “we are all one” — a recipe for high social capital and civic well-being, according to Haidt.

More from Haidt: Liberal Messaging of Sanctity

The Christian Right uses the Sanctity/degradation foundation to condemn hedonism and sexual “deviance.” Haidt acknowledges (however meekly) that the Sanctity foundation can, and should, be harnessed for progressive causes. Sanctity does not have to come from God. Liberals could do a better job of reframing the ugliness of un-restrained free markets as a moral issue. Environmental and animal welfare could be “messaged” as issues of Sanctity, not just appeals to the Care foundation.

“Soft On Crime” is a Disqualification

Democrats will have the most difficulty using the Authority foundation, according to Haidt. This foundation is about maintaining social order, so any candidate seen as “soft on crime” will disqualify himself or herself for many Americans. Haidt says Democrats should consider the quasi-religious importance of the criminal justice system. A party perceived to tolerate cheaters and slackers will be committing a kind of blasphemy.

“Defund Police” Violates Conservative Sacred Value

Politicians and pundits are debating the influence of the slogan “defund the police” on the down-ballot races in the November 2020 election. (“Defund the police” was first used in May 2020 during the George Floyd, Black Lives Matter protests.) Many prominent Democrats (e.g., Barack Obama, Jim Clyburn, Cory Booker, and Joe Biden) opposed using the term and articulated policies for police reform and reallocation of police resources. Most observers suspect that “defund the police” turned-off moderate voters and hurt the electoral chances of Democrats.

A Stupid Campaign Slogan

Ibram Kendi recently claimed in the Atlantic (December 3, “Stop Scapegoating Progressives”) that we don’t know if “defund the police” hurt Democrats, while also sharing polling data that sixty-four percent of Americans were opposed to it. Political scientist, Bernard Grofman, wrote that “defund the police is the second stupidest campaign slogan any Democrat has uttered in the twenty-first century” (second only to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 comment that half of Trump’s supporters belong in a “basket of deplorables,” which was not used as a campaign slogan).

Unity vs. Justice – The Moral Foundation Divide

An interviewer recently asked Abigail Spanberger (newly re-elected moderate Democrat in Virginia) and Ayanna Pressley (re-elected progressive Democrat in Massachusetts) the advisability of promoting “defund the police.” Both did a pivot and would not address the inaccuracy and political toxicity of that message. But Pressley framed the Democratic allegiance to Care/harm and Fairness/cheating foundations as distinct from the conservative Loyalty foundation. She told the interviewer, “it [the issue of Black Lives Matter and defund the police] is not about unity; it is about justice.” It could not have been more clearly illustrated: unity is a conservative sacred value, justice is a liberal sacred value.

Messaging Lessons Learned

There are six insights related to “defund-the-police” messaging:

- Repeating a message dramatically influences perception and cognition.

- The Black Lives Matter movement has used messages that are politically inadvisable and not descriptive of policies.

- Democrat representatives will avoid talking about this slogan directly; it is an undiscussable.

- Republicans will coopt whatever message increases the political divide and will vilify and lie about the reality of Democrat positions.

- “Defunding the police” violates the sacred value of the Authority foundation held by conservatives and many other Americans.

- Unity vs. justice is an unavoidable interdependent polarity that illustrates our political divide and the complexity of e pluribus unum.**

Guard the Coherent Whole of a Young Nation

Haidt recognizes that “democrats would lose their souls if they ever abandoned their commitment to social justice, but the divisive struggle among the parts must be balanced by a clear and often repeated commitment to guarding the coherence of the whole.” Haidt reminds us that America lacks the long history, small size, and ethnic homogeneity that holds many other nations together. So our flag, founding fathers, military, and common language take on a moral importance that many liberals have difficulty comprehending. (That said, disputing a legitimate election is a dramatic threat to the “coherent whole” of America and its relatively young democracy.)

Structure Restrains In the Service of Liberation

Conservatives believe that people need external structures or constraints to behave well, cooperate, and thrive. These external constraints include laws, institutions, customs, traditions, nations, and religions. Given twenty years of experience in group process design, facilitation, and agenda development, I concur entirely. The structure of an agenda (co-developed with the group leader or entire group) frames the order and effectiveness of problem-solving and helps people stay on-task and on-topic. Without a cogent, planned agenda and strong facilitation, groups flounder and spin their wheels in time-wasting chaos. Organizational development consultants and artists of all types understand that restraints and boundaries “at the edges” promote creativity instead of impeding it.

Blind Spots Around Freedom

Peter Ditto is a research colleague of Haidt’s who studies “hot cognition” – the interface between passion and reason. He says both conservatives and liberals have a blind spot around freedom. As mentioned in my last post, conservatives push for economic freedom but not freedom for things they think are morally wrong, like gay marriage or abortions. Liberals show precisely the opposite: they are comfortable with freedom regarding sexual behavior, and less so in economic behavior.

My Disagreements with Haidt:

- Haidt underestimates liberals’ connection to Sanctity/degradation foundation (e.g., food and environment).

- Haidt overestimates the conservative expression of the Care/harm foundation and does not fully acknowledge that conservatives do not prioritize it. We see the Republican deficit in Care/harm clearly expressed in their recent Covid-19 relief proposals: no direct cash given to vulnerable Americans but liability protections given to corporations. (This changed in the final bill.)

- Haidt underplays the force of money as a self-interest for conservatives. Conservatives’ in-group loyalty is most vital with those of higher socio-economic status — conservative/Republicans at the top of the hierarchy. Haidt appears to underestimate, or not clearly articulate, the power of monied interests in the conservative/Republican tribe.

- Haidt seems to claim that when Republicans vote for their economic interests, it is from a Fairness-proportionality foundation and not from trying to protect their privileged (self-interested) hierarchical position. It is undoubtedly both. Conservatives are worried about the perceived lack of proportionality related to programs and taxes that serve the lower class, but not the absence of proportionality of the middle and lower classes compared to the upper socio-economic class. The salary disparities between CEOs and line workers are ignored or rationalized as necessary. There seems to be a blind spot for conservatives within the Fairness foundation. According to recent federal data, the top 1% of Americans hold 30.4% of all household wealth in the US, while the bottom 50% hold just 1.9% of all wealth. Is it proportionate for the 50 most affluent American families to own as much wealth as the poorest 165 million? (Bloomberg Wealth, October 8, 2020).

- Haidt asserts that “everyone goes blind with sacred objects.” While this point has merit for understanding human cognitive processing, Haidt’s exposition on this point succumbs to a bit of false equivalency (which he could not have foreseen at the time of the book’s release.) Democrats are not as blind to science, reason, and common sense as QAnon right-wing extremists and a significant portion of the Republican base. Donald Trump lied to the American people approximately 30,000 times and broke many American norms of civility and stewardship for an American President.

- Haidt made an immense contribution with Moral Foundation Theory but overcorrected in his politically correct message to liberals, who, he knows, will actually listen to reasoning. This (rational) appeal to liberals illustrates a perceived difference between a liberal and a conservative, disproving the very argument of equivalency (“everyone is blind”) Haidt seems to be making.

What is Moral Capital?

Haidt defines moral capital as “the resources that sustain a moral community — values, norms, practices, identities, institutions, and technologies that mesh well with evolved psychological mechanisms and thereby enable the community to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperation possible.”

“Moral Capital” Can Be Good or Destructive

Moral capital, says Haidt, is “not always an unalloyed good.” It leads to the suppression of free riders, but it does not lead automatically to other forms of fairness, such as equal opportunity. And while high moral capital helps a community to function efficiently, the community can use that efficiency to inflict harm on other communities. High moral capital can be obtained within a cult or a fascist nation, as long as people accept the prevailing moral matrix.

Conservative Failures

Conservatives, says Haidt, do a better job of preserving moral capital but often fail to notice certain classes of victims, fail to limit the predation of powerful interests, and fail to see the need to change or upgrade institutions. Conservativism may be used to maintain cultural cohesion, but the conservative moral matrix potentially includes violence, subjugation, and inequity in the development of social hierarchies and nation-states.

Liberals Change Things Too quickly

Haidt’s “tough-love letter” to liberals reminds them that if they do not consider the effects of changes on moral capital, they are asking for trouble. Haidt believes this is the fundamental blind spot of the Left. It explains, he says, why liberal reforms backfire and why communist revolutions end up in despotism. Haidt acknowledges that liberalism has done a lot to bring about freedom and equal opportunity but asserts that liberalism is not a sufficient governing philosophy. It tends to overreach, change too many things too quickly, and “reduce the stock of moral capital inadvertently.”

But Liberals Should Restrain Corporations and Regulate

Haidt says that liberals make two points that are profoundly important for the health of a society: 1) governments can and should restrain corporate superorganisms, and 2) some big problems really can be solved by regulation.

Yin and Yang of Our Political Landscape

A party of order or stability and a party of progress or reform are both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life.”

~John Stuart Mill

Our democracy and psycho-social well-being need both a liberal and conservative framework. Like yin and yang, both are necessary elements of a healthy state of political life. Liberals are better able to see the victims of existing social arrangements as they push to update those arrangements and invent new ones. Conservatives sustain the institutions that bind and preserve a community. “I see liberalism and conservatism as opposing principles that work well when in balance,” says Haidt. “Authority needs be to both upheld and challenged. It’s a basic design principle. You get better responsiveness if you have two systems pushing against each other.”

Two Approaches for Living in Peace

There are two approaches to having unrelated people create a society where they live together in peace – two philosophies that undergird liberals and conservatives, respectively: prevent harm to others and be loyal to the group.

1. Prevent Harm To Others

Renowned British philosopher, John Stuart Mill, wrote (in On Liberty), “the only purpose for which power can be exercised over any member of a civilized community against his will is to prevent harm to others.” Mill’s ideas about governing a society of autonomous individuals essentially describe the liberal Care/harm foundation and the libertarian Liberty/oppression foundation.

2. Preserve the Family – Be Loyal To the Group

Emile Durkheim had a different vision from Mill. The basic social unit is not the individual, it is the hierarchically structured family, which serves as a model for other institutions. (See George Lakoff’s Strict Father Family Model in Part 2.) Individuals are born into strong constraining relationships that profoundly limit their autonomy. A Durkheimian society values self-control over self-expression, duty over rights, and loyalty to one’s group over concerns for out-groups. A Durkheim world, says Haidt, can be unusually hierarchical, punitive, and religious.

In-group versus Out-group, Again

Mill’s liberal vision would allow care for out-groups. Durkheim’s conservative vision would not; loyalty and authority are given only to the in-group. The modern-day conservative vision is focused heavily on in-group hierarchy, which allows the expression of economic self-interest, perhaps sometimes masquerading as Mill’s individualism. Folks at the top of the hierarchy often revere the individualism of economic self-interest.**

Self-interest vs. the Common Good

Modern-day liberals see the community, the common good, as an extension of the family, whereas modern-day conservatives in America promote individual rights and self-interest over community rights. Conservatives advocate for individual liberty in economic and social policy in opposition to the “common good” for the larger community of diverse groups.**

The Miracle of E Pluribus Unum

Haidt says that if your moral matrix rests entirely on the Care and Fairness foundations, then it is hard to hear the sacred overtones in America’s unofficial motto: E pluribus unum (“out of many, one”). Haidt says that the process of converting pluribus (diverse people) into unum (a nation) is a miracle that occurs in every country on earth. Nations decline or divide when they stop performing that miracle.

Human Nature, Belief, and Belonging

We are 90% Chimp and 10% Bee

Humans have a dual nature — we are selfish primates who also long to be part of something larger and nobler than ourselves. We are 90% chimp and 10% bee. We have the ability under special conditions to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves, temporarily and ecstatically, in something larger than ourselves. This ability is the “hive switch” — an adaptation for making groups more cohesive and therefore more successful in competition with other groups.

Collective Effervescence

Durkheim calls this inter-social sentiment “collective effervescence” — the passion and ecstasy generated by group rituals. These collective emotions pull humans fully, but temporarily, into the realm of the sacred where the self disappears and collective interests predominate. “The very act of congregating is a potent stimulant. Once individuals gather together, a sort of electricity is generated from their closeness and quickly launches them to an extraordinary height of exaltation.” (I have witnessed this in a Christian mega-church and a Christian evangelical black church. In both, the music was a powerful trigger.)

Football and Religion

Durkheim saw the function of religious rituals as the creation of community. The college (or pro) football game is a superb analogy for religion. Football games flip the hive switch and make people feel, for a few hours, that they are simply part of a whole. The ball movement and the plays are like the content or beliefs of religion – they are important details, but not the emotional reason for the game.

New Atheists

The New Atheist model of religious psychology came as a response to the attacks on 9/11 and was led by Sam Harris’ End of Faith, Richard Dawkin’s The God Delusion, and Daniel Dennett’s Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. For these authors, beliefs were crucial for understanding the psychology of religion. Believing a falsehood, they said, makes religious people do harmful things — “believing” causes “doing.”

Belief is Not the Social Facts

The focus on belief is not unique to the New Atheists. It is familiar to psychologists, biologists, and other natural scientists. Sociologists, anthropologists, and scholars in religious studies have a different view. They are more skilled at thinking about what Durkheim called “social facts.”

Trying to understand the persistence and passion of religion by studying beliefs about God is like trying to understand the persistence and passion of college football by studying the movement of the ball.

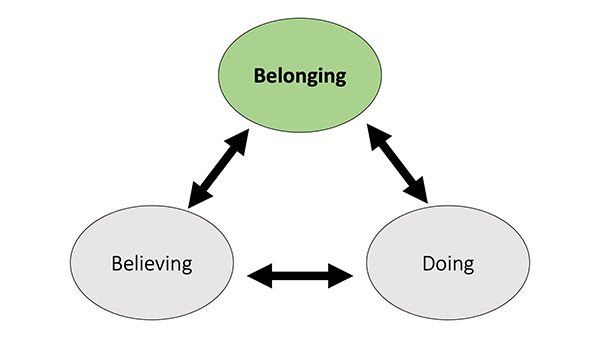

Bottom line: Belonging is More Important than Beliefs

Durkheim sees “belonging,” “believing,” and “doing” as three complementary yet distinct aspects of religiosity. But belonging is the key; belonging informs belief and action. The function of beliefs and practices is ultimately to create a community. Belonging was palpable in my experience of the Christian churches and even more so in a Jewish congregation with my then-girlfriend, Maureen.

Belonging Is the Opposite of “Hunkering Down”

Belonging is an antidote to the alienation described by Robert Putnam. No one wants to bowl alone. Belonging is the opposite of “hunkering down.” Belonging (paradoxically) drives liberal identity politics. All colors of the rainbow look for their own rainbow coalition. Individual “snowflakes” actually want to feel connected to similar snowflakes more than they want to be so different that they are alone. Belonging drives our social media obsessions and increases the psychological risk of “fitting in” during early adolescence, especially for girls.

Belonging is Fundamental to Homo Sapiens

Belonging drives our religious experience and our political affiliations. The white race is now shrinking in proportion to the entire US population. Some want to belong to it more stridently than ever. Belonging to a group and family is fundamental for human beings. Belonging is part of our evolutionary DNA. If a hunter got banished from the tribe, he died alone on the savannah. Individual strands of rope will shred and break. But the collective strands of rope can get into a nasty knot. Yes, “out of many, one” is complicated.

Notes

*Ten Insights of Jonathan Haidt from Part 3

1. Intuitions come first, reasoning second.

2. There is more to morality than harm and fairness.

3. Pluralism is not relativism.

4. Morality binds and blinds.

5. We have a “hive switch.”

6. We are not as divided in politics as the moral dualists would have you believe (pre-Trump).

7. We are deeply intuitive creatures.

8. It is hard to connect with those who live in different moral matrices.

9. Look for commonalities.

10. Some things are sacred to others as some things are sacred to you.

**Self-interest vs. The Common Good: E Pluribus Unum is Complicated

In my last post, I explained the apparent paradox of the human predilection for both hierarchy and egalitarianism. I presented evidence that we are primarily structured for hierarchy but have been egalitarian in our evolutionary past. In a parallel way, we see that humans are mostly driven by self-interest and in-group interests. But if triggered, humans can be more inclusive and share an experience of “the hive” — an experience of the larger collective. Moral Foundation Theory research has found that liberals are more prone to include the entire hive in their moral calculations. But clarity about individualism or self-interest vs. the interest of the “common good” of the larger community can be tricky within Haidt’s Moral Foundation Theory.

Venn Diagram of Liberals

If we were to imagine a two-circle Venn diagram of the liberal consideration of in-group and out-group, we would see a large overlap of the two circles. The in-group would reach further into the circle of “others” (out-group) and the intersection in the middle would be a large area of cooperation and experience of the collective “hive”.

Liberals are often associated (the “me-generation,” et. al) with the idea of individualism. As presented in modern-day identity politics, there are “snowflakes” of every type. This is “the many” (pluribus) individuals that include the rainbow of human diversity, the “people of difference” who are more outside the mainstream. The liberal Venn diagram displays more xenophilia and less xenophobia. In this framing, “the many” is the common good — the community that includes a multitude of unique individual self-interests.

Venn Diagram of Conservatives

The Venn diagram circles for conservatives look much different. The in-group and the out-group circles do not overlap at all. There is a xenophobic space between them. Here’s the tricky part: Conservatives have allegiance for the in-group as expressed by their Loyalty and Authority foundations. Their sacred value is “the one” (unum) nation that overrides the individual interests of “the many.” But the conservative in-group is structured by hierarchy. And the hierarchy promotes the self-interest of those holding rank and status at the top. It is also clear that their in-group is above the out-group – a further expression of hierarchy predicted by evolutionary history. Within the conservative in-group, there can be moments of dissolution of self-interest that produce cooperation for the “hive” through religion and political cultism.

Structured for Hierarchy Wins the Day

In practice, conservatives promote the interests of the one, sacred in-group, and liberals promote cultural individualism and individual justice for the many. The human predisposition to be “structured for hierarchy” wins the day in contemporary American democracy. Conservatives promote the self-interest of those with social-economic power and status and liberals promote the “common good” – human rights and justice of those lower on the socio-economic hierarchy.

Paradox of Power

As a final wrinkle, UC Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner argues (The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence) that we rise in a social hierarchy and gain power and reputation by positively influencing the lives of others (unless you were born rich). But once humans gain power, they become much less relational and empathic. “We rise in power and make a difference in the world due to what is best about human nature, but we fall from power due to what is worst,” says Keltner. His research ultimately supports John Dalberg-Acton’s oft quoted insight that “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Please Note: Your comment may take up to 12 seconds to register and the confirmation message will appear above the “Submit a Comment” text.

Lots to reflect on in this post, Steven! I kept having flashes of new insight and connection as I read through the post. It helped me to see the powerful benefits which come from the moral foundations of loyalty, authority, and sanctity as a means of building ever larger, more complex, yet coherent groups of people who can connect and affiliate well beyond the more basic family and tribal contexts. I can see how a focus on “universality” may be much easier to espouse for those who have benefited from the current structures and who can, thus, see more diversity as a welcome force rather than a threatening one. What can function as unifying and motivating forces when the “unity” begins to fray–especially for those whose lives are under great stress already? Thanks for pulling this together and stimulating so many new questions!